This resource is provided by ACSA Partner4Purpose Lozano Smith.

A recent U.S. District Court decision out of Washington State provides clarification regarding how school districts are to apply their sexual harassment policies and analyze conduct as it relates to students with disabilities. Specifically, the decision in Berg v. Bethel School District (W.D. Wash., Mar. 16, 2022, No. 3:18-CV-5345-BHS) clarifies that a school district is required to protect students with disabilities from sexual harassment, even if the student does not specifically object to the conduct.

Background

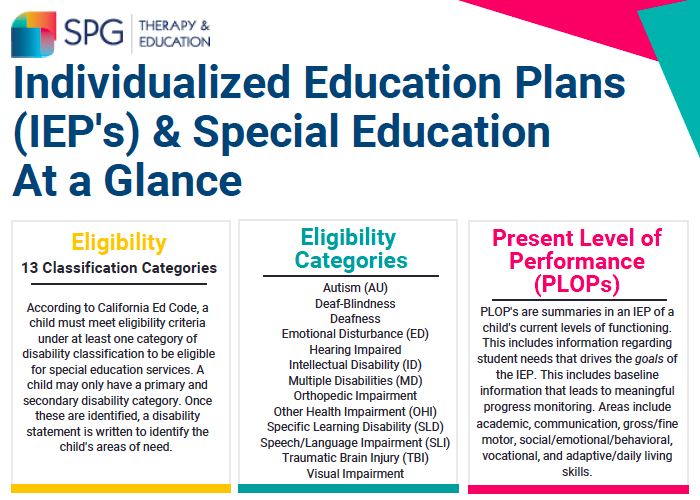

During the 2012-2013 school year, a special education student (Plaintiff) at Bethel School District (District) was subjected to sexual harassment by another special education student that ultimately led to sexual assault. Plaintiff filed suit against the District, alleging the District violated the Plaintiff’s Due Process and Equal Protection rights, Title IX, Washington State’s anti-discrimination law, and was negligent. Plaintiff alleged, among other things, that the District was aware of the perpetrator’s extensive history of sexual assaults against other special needs students and failed to protect her from the known risk of harm. Following an eleven-day jury trial and a $500,000 verdict for Plaintiff, the District moved for judgment as a matter of law, arguing that Plaintiff’s cause of action for violation of the Equal Protection Clause failed because the District’s sexual harassment policy had a rational basis as a matter of law. On March 16, 2022, the court denied the District’s motion.

The evidence at trial demonstrated that the District’s sexual harassment policy required students to object to the sexual harassment. Plaintiff argued that she could not object because of her cognitive disabilities. The court upheld the jury’s finding that the District’s policy discriminated against students with disabilities by treating them differently from the way it treated typically functioning students, and that the policy did not have a rational basis, therefore violating Plaintiff’s Equal Protection rights.

The court upheld the jury’s finding that the District failed to report the perpetrator’s abuse, and that this failure to report was a contributing factor in Plaintiff’s injury. The jury’s finding included that the Superintendent acted either intentionally or with deliberate indifference, which is the liability standard applied to Title IX cases. In its decision, the court highlighted that even if the Superintendent was not aware of the specific incident of sexual assault against Plaintiff, there was substantial evidence that, given the number of other complaints and incidents of known sexual harassment by the perpetrator against other students with disabilities, the Superintendent and his subordinates were aware of the perpetrator’s “continuing, abusive behavior” and that the District had therefore violated the Plaintiff’s Due Process rights.

Takeaways

Though this case was decided outside of California, it provides a helpful reminder to school districts regarding the interplay between special education and sexual harassment laws, including Title IX. Under both state and federal law, school districts are required to protect all students from sexual harassment, including those with disabilities. How consent is defined in school district sexual harassment policies should be examined, specifically taking into how the policy determines whether conduct is unwelcome in the context of persons with different cognitive abilities. This case clarifies that a consent policy should not require a person to object to conduct for it to be considered nonconsensual. This case also highlights that even though the Superintendent may not have actual knowledge of a specific incident of sexual assault, the district may ultimately be held liable for a failure to respond to ongoing sexual harassment.

If you have any questions about this District Court decision, or about sexual harassment policies, Title IX, or related issues in general, please contact the authors of this Client News Brief or an attorney at one of Lozano Smith’s eight offices located statewide.