By Rachael Ding

Introduction to the issue of special educator burnout

Over the past decades, a general trend for a shortage of teachers in certain subjects has raised awareness about the difficulties of teaching, and how public school systems need to improve working conditions and compensation. This impact trickles down to students who are negatively affected by high teacher turnover rates (Ronfeldt et al., 2013; Gibbons et al., 2018).

Special educators lay at the extreme of high burnout rates (Emery & Vandenberg, 2010; Y. L. Lee et al., 2011). This has led to a shortage of special educators (Fore et al., 2002; Leko & Smith, 2010). In establishing the criticality of the problem, Darling-Hammond et al. (2018) displayed a greater than 50 percent decrease in new teacher candidates, with special education being one of the areas hit hardest. This is contextualized by the fact that the special-needs student population has been increasing (US Department of Education, 1990), with the number of BA’s in special education decreasing (NASDSE, 1990).

Past studies, including Wong et al., (2017) have delineated a connection between burnout and high turnover rates, or attrition of teaching professionals. Burnout is a proven leading cause.

Background on previous research

A previous study published in ACSA Education California Volume 53 Issue 22 on April 10, 2023 consisted of 100 special educators from Northern California, teaching grades 9-12. The study asked special educators to report levels of administrative support in six areas: case management support, classroom support, communication support, mental health support, positive environment, and opportunities for growth. Analysis was then conducted using Structural Equation Modeling and regression analysis.

The study showed that the top three types of administrative support influencing burnout levels the most were (in descending order):

- Positive Environment

- Opportunities for Growth

- Mental Health Support

In addition, the top three types of administrative support that impacted turnover were:

- Case Management Support

- Opportunities for Growth

- Classroom Support (support with teaching duties i.e. adequate materials, aids)

With this study in mind, this report seeks to build on these findings with a real-life case study of the Fremont Union High School District. It looks at the impact of three newly implemented support programs during the 2022-23 academic school year. It also highlights how data-backed practices might improve working conditions for special educators and foster a supportive environment in order to mitigate burnout and turnover.

Background on FUHSD

Fremont Union High School District is located in Santa Clara County, serving 10,836 (2020-21) students. Sixty-eight special educators work in the district among five high schools (teaching grades 9-12), one alternative high school site, and an adult school.

In the 2022-23 school year, the district administration sent out two surveys, one in fall and one in spring, to special educators in the district. During this period, three new support programs were implemented for special educators (covering three out of six types of support identified in the previous study):

Opportunities for Growth: Professional development efforts with designated professional development Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA).

Case Management Support: TOSA Program that hired additional staff to help with IEP paperwork.

Mental Health Support: Staff Wellness Program to provide additional mental health resources.

A summary of the six types of administrative support and the feedback from FUHSD teachers in both cohorts is shown below:

| Type of Support | Summary of FUHSD Special Educator Responses | Current FUHSD Initiative |

| Case Management | Special educators felt that there was not enough time to case manage and teach. | Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA) program (Started August 2022)

|

| Communication | Special educators felt that general educators didn’t respond to norunderstand special education communications (i.e. IEP accommodations and requirements). | N/A |

| Classroom | Special educators feel that facilities were not designed for special education. | Staff Wellness Program (Started August 2022)

|

| Mental Health | Special educators reported that it was a new focus that most did not know about or did not utilize. | |

| Positive Environment | Special educators had mixed responses with a cohort of teachers feeling that general education is valued more than special education. | N/A |

| Opportunities for Growth | Special educators reported that the mentorship system was good at FUHSD schools and were mostly excited for the new Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA) dedicated to professional development. | Charity Purse with Professional Development (Started August 2022)

|

Fifty-nine responses were received in October/November (referred to as ‘Cohort A’, and an additional 7 were received in April/May (referred to as ‘Cohort B’). Data was then compared using statistical tools and qualitative measurements. Findings from the previous study outlined above were also utilized to understand comparison results between Cohort A and Cohort B.

Findings

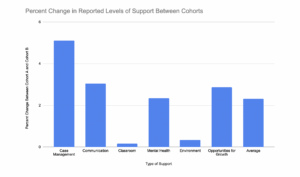

Differences between the two cohorts of special educators are illustrated below:

- The average number of years of experience in special education increased by 5.92myears from Cohort A to Cohort B (Cohort B had more senior special educators represented than Cohort A)

- The average amount of support reported increased by 2.08% from Cohort A to Cohort B

- The following types of support each increased by more than 2% between cohorts:

- Case Management Support: 5.12% increase

- Communication Support: 3.05% increase

- Opportunities for Growth: 2.87% increase

Opportunities for Growth

FUHSD appointed a TOSA on special education professional development in the 2022-2023 school year. A professional development TOSA was hired to organize workshops and answer questions for special educators exclusively.

Comments from special educators on the professional development program:

- “[The professional development TOSA] is fantastic. She is my mentor and very supportive. Any question is answered and she does not judge me. I feel comfortable coming to her with any questions or concerns. Her door is always open. She is welcoming and very supportive.”

- “FUHSD has provided the opportunity to receive funding through school site council for professional development seminars as well as through special education funds. They are also in the process of developing professional development designed specifically for special education teachers and will have the first special education professional development in Feb 2023. They have designated a teacher on special assignment to create the professional development with input from district special ed staff. This is a first and a great step in providing more opportunities for professional growth in order to support students.”

Corroborating the teachers’ comments, the level of reported Opportunities for Growth increased by 2.87% between Cohort A and Cohort B. This suggests that increasing professional development activities for special educators helps their classroom practices and their feeling of support. Additional concerns on Opportunities for Growth from teachers acknowledge the importance, as well as barriers, in providing effective professional development that seeks input from special educators directly. For example, special educators find they don’t have time to seek out or go to professional development opportunities as they are already overwhelmed with other non-teaching activities like case management and testing. Others mention that it would be great to be able to share curriculum and lesson ideas with other special educators.

Case Management Support

The TOSA program introduced at two high schools within FUHSD featured staff hired to directly handle IEP paperwork. This lessened the case management workload of special educators significantly, allowing them to use prep periods on lesson prep. It also helped relieve the time pressure of IEPs and improved special educators’ mental health.

Comments from special educators on the TOSA program:

- “This year is the first time we have implemented a systematic change to how we manage IEPs at two of the sites in our district. We have created a new IEP Manager position and this person is responsible for writing all annual and triennial IEPs for up to 112 special education students at our respective sites. This has made a huge positive impact on special education teachers—they are now able to focus more on their teaching and effective case management without having to worry about doing all the paperwork that comes with special education students.”

- “The TOSA program has relieved a lot of stress and given me more time to lesson plan and case manage. Not having to be responsible for writing every IEP for the students on my caseload has been amazing.”

Corroborating the teachers’ comments, the level of reported Case Management Support increased by 5.12% between Cohort A and Cohort B. FUHSD special educators also mentioned that communication and relationships with families as part of the IEP process was important but could be difficult. Moreover, a positive aspect special educators benefited from was a robust mentorship system at FUHSD that helped new special educators with case management, which many special educators mentioned they were not prepared for when going into special education.

Mental Health Support

The Staff Wellness Program is a mental health program offered to all educators in FUHSD, including special educators. It was implemented in August of the 2022-2023 academic year. Feedback from special educators on the Staff Wellness Program include:

- “I believe our district provides a really good range of mental health supports, it is just finding the time to use them.”

- “We had training at the beginning of the year by an outside organization that offers therapy services to teachers for free. I didn’t sign up but I thought it was great that this service was offered. I think our insurance plan also covers free therapy so that is nice as well.”

The data displays that between the two cohorts, the reported level of mental health support increased by 2.35%. Other comments from special educators illustrate some of the challenges of getting mental health support and the crucial aspect of feeling valued at work. For example, teachers mention not having enough time to access mental health support or uninformed of current programs that were available. Also, special educators often mentioned how much they perceived the administration and school cared about them aided their feeling of belonging and as a result, their level of perceived support for their mental health. Moreover, decreasing the amount of stress from time pressure could have also aided special educators in FUHSD in feeling more positive about their mental health status.

Conclusions

The first aspect to consider when implementing support programs for special educators is the response of educators to receiving new supports. The educator’s perception of their working environment is critical to fostering a good environment. Various reactions from special educators to FUHSD’s new programs included:

- A general positive response

- Uneven awareness of supports with some teachers actively seeking out and using supports and others unable to/ignorant of

- Most special educators were hesitantly hopeful

- Some were negatively biased, expressing in the survey that they expected the supports not to work due to past negative experiences or perceived lack of promise

Furthermore, it’s important to receive educator feedback before, during, and after the process in order to evaluate the direction support programs should follow and their effectiveness. For FUHSD, continuous teacher input and a working dialogue with administrators on school and district levels enabled successful support programs to be introduced. This data-backed and inclusive approach ensures that supports work and teachers feel they are in a caring, supportive work environment.

Further ideas on possible support programs

Other support programs districts can consider when evaluating the needs of their special educator populations include improving channels of communication and building a positive environment.

Firstly, spreading awareness of available support systems, ensuring a steady flow of feedback on their efficacy, and enhancing communication channels are crucial in addressing the needs of special educators. To achieve these goals, districts can establish a centralized website that offers comprehensive professional development opportunities and mental health resources.

Regular newsletters, whether scheduled bi-annually, quarterly, or monthly, can also be a platform for administrators to share resources and support. Strengthening communication channels at all levels, from district level initiatives to individual schools and teachers, ensures a seamless exchange of information. This can further help special educators feel heard and recognized.

Moreover, to promote inclusivity and collaboration, districts can emphasize school-wide communication channels that incorporate perspectives from both general education and special education. Also, ensuring that general education teachers are well-versed in the legalities surrounding Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and 504 plans is essential. To achieve this, districts can organize advisory sessions or professional development workshops specifically tailored for general education teachers, providing them with insights into special education basics. Additionally, periodic reminders from administration about legal requirements can help maintain a strong awareness of these obligations and foster an environment of compliance and support.

And finally, building a sense of community among educators is vital, and districts can achieve this through various social initiatives. By organizing inclusive social events, both within and beyond departments, districts and schools can strengthen connections among educators.

Additionally, creating opportunities for educators to learn from one another, especially from more experienced educators, can greatly enrich teaching practices. For example, hosting events such as “shake-up days” where educators visit different sites and classrooms can encourage collaboration.

Rachael Ding is a senior at Monta Vista High School (Fremont Union High School District) and a commissioner on the California State Advisory Commission on Special Education (ACSE).

References

Darling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher Shortages in California: Status, Sources, and Potential Solutions. Research Brief. Learning Policy Institute.

Emery, D. W., & Vandenberg, B. (2010). Special Education Teacher Burnout and ACT. International journal of special education, 25(3), 119-131.

Fore, C., Martin, C., & Bender, W. N. (2002). Teacher burnout in special education: The causes and the recommended solutions. The High School Journal, 86(1), 36-44.

Gibbons, S., Scrutinio, V., & Telhaj, S. (2018). Teacher turnover: Does it matter for pupil achievement?.

Klassen, R., Wilson, E., Siu, A. F., Hannok, W., Wong, M. W., Wongsri, N., … & Jansem, A. (2013). Preservice teachers’ work stress, self-efficacy, and occupational commitment in four countries. European journal of psychology of education, 28(4), 1289-1309.

Lee, Y. L., Patterson, P. P., & Vega, L. A. (2011). Perils to self efficacy perceptions and teacher-preparation quality among special education intern teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38, 61–76.

Leko, M. M., & Smith, S. W. (2010). Current Topics in Review Andrea M. Babkie, Associate Editor: Retaining Beginning Special Educators: What Should Administrators Know and Do?. Intervention in School and Clinic, 45(5), 321-325.

National Association of State Directors of Special Education. NASDSE. (1990). Retrieved January 2023, from https://nasdse.org/

Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American educational research journal, 50(1), 4-36.

US Department of Education (1990). Twelfth annual report to Congress on the implementation of Public Law 94-142: The Education for all Handicapped Children Act. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Leave a Comment