By Dr. Gina Arias

Over the past decade, like many other educators, I have been provided with multiple professional development courses that aimed to help content area teams work more collaboratively in a professional learning community (PLC). And like many other educators, I did my best but often found myself doing the business of education as usual: working in department teams to check-in, making sure we were all working on standards or keeping to the pacing guide, mostly in isolation. This is what the PLC experts at Solution Tree call PLC Lite, (Muhammad, 2024), well-meaning educators who are not really participating in the work of a functional and productive PLC, but rather only attending department and whole staff meetings and labeling these as PLC meetings (Muhammad, 2024).

The term professional learning community (PLC) has been misinterpreted and misused by many educational institutions. Too often schools mistakenly call themselves professional learning communities not understanding the true meaning of the term (DuFour, DuFour, & Eaker, 2008). Professional learning communities are not defined by whether or not professional development sessions are provided, weekly meetings are conducted, or if analysis of data occurred. Which is unfortunate because professional learning communities can drastically improve the outcomes and cultures of educational institutions. DuFour, DuFour, & Eaker (2009), explain that effective PLCs shift their emphasis from teacher-centered instruction to student-centered learning by prioritizing what students have learned and demonstrated, rather than simply what was covered in class. Assessments shift from summative to formative to determine students needing additional support, rather than who passed and who failed the exam. Teachers move from isolated classrooms to collaborative environments. Educators work in teams, sharing knowledge and building understanding about effective practices ensuring student learning. Students move from invitational support outside of the school day toward required support during the school day.

Educators within a PLC are each committed to the improvement of student achievement by working collaboratively with colleagues through action research and collective inquiry (DuFour et al., 2008). PLC educators understand that continuous improvement for students requires teachers to continuously work alongside one another analyzing student data, creating interventions, creating common assessments and goals, and aligning curriculum vertically and horizontally. This is the challenging, ongoing work of functional PLCs — not just something addressed during staff meetings.

Establishing and sustaining an authentic professional learning community takes a great deal of work, and it is not solely the responsibility of teachers to make it happen. Supportive school leadership can provide appropriate time for collaboration, a safe environment, and ensure sufficient time for collaboration (Yusra, J. A.K., Raghad, A., Adnan, A.A.A., Haitham, M.E., Mohammad, N.A. & Mohamad, A.S.K., 2023). School leaders can create and support conditions that help staff build and improve collaborative capacity, disperse leadership throughout the school, and align the culture with the vision (DuFour et al., 2008). Collaborative capacity refers to the ability of staff to come together with knowledge, motivation, and skills to improve collective and individual results. Without strong school leadership, it can be difficult to engage in authentic PLC work, no matter how practical a framework or how motivated the teachers.

Professional learning communities are most effective when both results-oriented approaches and inquiry-oriented approaches are utilized (Jacobson, 2010). In the inquiry-oriented approach teachers identify issues, pose questions, collect data, and conduct research into new strategies that can help change and improve classroom practice (Jacobson, 2010). The results-oriented approach consists of vertical and horizontal alignment through grade-level teams and content-area teams. “Integral to this agenda are two activities: determining what’s most important for students to learn (often called essential standards or learning targets) and developing and analyzing common formative assessments” (Jacobson, 2010, p. 39). Then, results-oriented PLCs work collaboratively to assign students to intervention groups or enrichment groups.

As valuable and effective as PLCs are in supporting student learning and increasing teacher job satisfaction (Yusra, et. Al, 2023), many educators struggle to shift from the isolated-teacher model to one of shared responsibility. Many of us are guided by state standards and a district pacing guide and use these to drive our practice instead of letting student data take the lead. Shifting the focus from what we teach to what students learn can be especially challenging when teachers feel they already have solid systems in place. It can be even more difficult in a PLC where members are not aligned in pacing, or in cross-curricular teams where no one teaches the same subject. Even worse, some PLCs include only a few members who are truly committed to working collaboratively. I have experienced these challenges myself, but when there is a will there is a way.

Our PLC had a will and so we made a way. We began building collaborative capacity by using weekly literacy learning targets and weekly common formative assessments to evaluate student learning. This strategy allowed us to engage in authentic PLC work through a shared focus on literacy. Regardless of the content or method of instruction, literacy could always be assessed. Whether a teacher felt isolated, lacked leadership support, or faced difficult scheduling, literacy could still be assessed. Some of the literacy learning targets we used included:

- Students are using content vocabulary appropriately to write a 3-5 sentence summary.

- Students can accurately describe a vocabulary term and draw a model of the meaning.

- Students can identify content vocabulary in an article and explain the relationship of a text to the content.

We developed quick, easy to implement and analyze formative assessments for these learning targets and analyzed student work together. One CFA example is the 3-2-1 Reflection, which can be given to students as an exit ticket, completed in less than 10 minutes and quickly analyzed. These practices allowed our team to collaborate toward a common goal and provided us with vital insight into student learning. When teachers collaborate, learning is enhanced, even if the learning goals are not content specific (Hudson, 2024). Over time, this literacy-based PLC focus led to the development of common content units using the same PLC protocol.

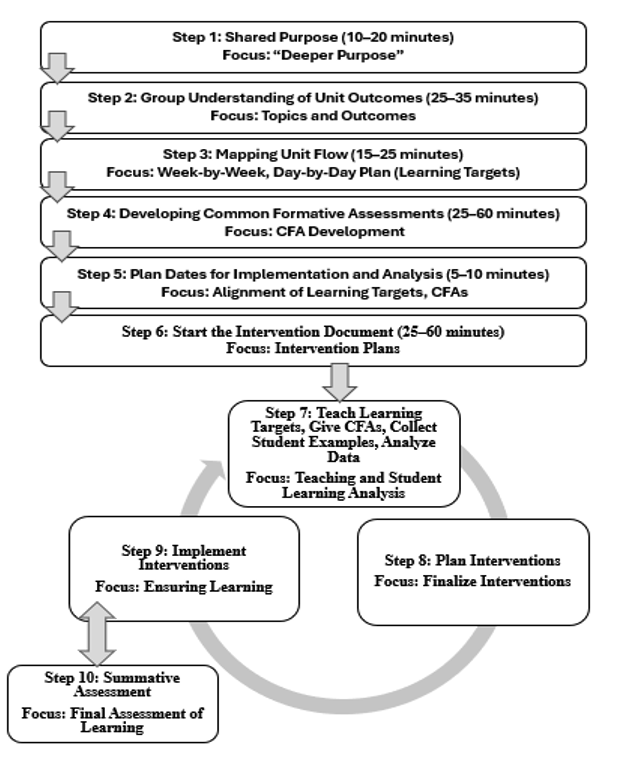

After years of professional development sessions, conferences, articles, and from working with evolving PLC teams, we developed a 10-step protocol that synthesized what we learned and experienced. The first six steps require dedicated collaborative time, ideally a teacher pull-out day. Steps 1-6 aide teachers in developing a common unit (either content-specific or literacy-based), establish learning targets, create common formative assessments (CFAs), and planning analysis and interventions. Steps 7-10 are cyclical involving the implementation of lessons and CFAs, student work analysis, and use of a Multi-Tier System of Supports for students who did not learn during the first round of interventions. Our team uses a once-a-week collaboration hour to analyze data and finalize the interventions in steps seven and eight.

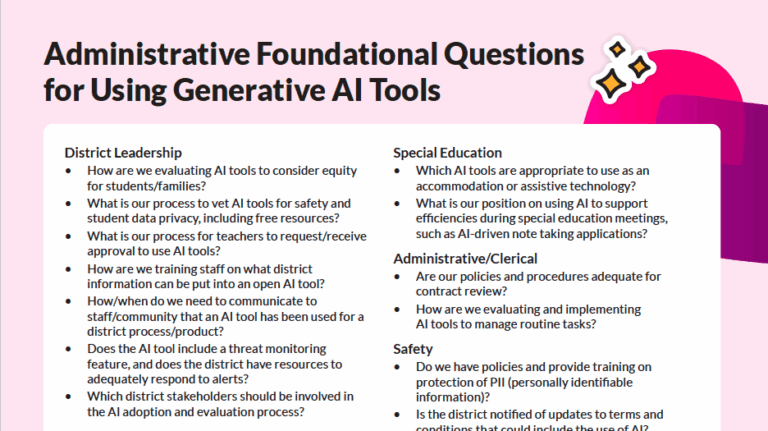

Collaborative PLC Protocol

This PLC protocol model shows the flow of steps involved. Times are provided as a guide, but some steps will need more or less time. Teams can modify as needed.

Collaborative PLC Protocol

Professional learning communities are collaborative and require teachers to step out from isolation into a sharing and open environment. An environment of trust and respect is a requirement for professional learning communities to be effective. Team norms can aid in trust between staff and should be established. “In PLCs, norms represent protocols or commitments developed by each team to guide members in working together. Norms help team members clarify expectations regarding how they will work together to achieve their shared goals” (DuFour et al., 2008, p. 471). Norms enable teachers to continuously work interdependently as a team with a common goal. Before collaborative inquiry begins, I would recommend establishing group norms. This can help ensure that all teachers have a voice and can help minimize the tangents some of our colleagues can engage in during focused group work.

Step 1: Shared Purpose (10–20 minutes)

Focus: “Deeper Purpose”

Begin by reviewing the unit standards (or literacy standards) together to ground the work in required learning goals. Individually, reflect on the standards and the unit’s content by writing responses to the following questions:

- What elements of this unit can be leveraged to better engage students or to deepen their connection to real-world issues?

- In what ways is this unit relevant to your students, or how might you modify it to ensure its relevance?

- What aspects of this unit have the potential to spark student curiosity and drive inquiry?

Once all participants have reflected individually, come together as a group and share your thoughts in a circle to build a collective understanding of the unit’s deeper purpose.

Step 2: Group Understanding of Unit Outcomes (25–35 minutes)

Focus: Topics and Outcomes

Start by independently reviewing the standards for five minutes. Then, as a group, work together (either digitally or on a poster) to complete the following:

- Identify which topics are explicitly covered in the standards and which are not but might be relevant.

- Define what students should be able to do with each of the selected topics—this becomes your set of unit outcomes.

- Determine the final product or deliverable students will produce, and make sure it clearly aligns with the established outcomes.

Step 3: Mapping Unit Flow (15–25 minutes)

Focus: Week-by-Week, Day-by-Day Plan (Learning Targets)

Collaboratively build a pacing map for the unit that spans three or more weeks.

- Prioritize topics by sorting them into three categories: essential topics (must-teach), topics you would love to teach (if time allows), and topics only to include if extra time is available. Or focus on the literacy outcomes your team will use to work collaboratively to ensure content area literacy.

- Establish clear, weekly Learning Targets that focus on what students should know and be able to do, rather than how the material will be taught. One of these learning targets will be the focus of the CFA for that week.

- Focus on learning, not on how the learning targets are taught. Teacher autonomy is an important part of this protocol so focus on the learning outcomes. Sharing best practices can occur later once collaborative capacity is established.

- For each learning target, identify potential Common Formative Assessments (CFAs) that will measure student progress and understanding.

Step 4: Developing Common Formative Assessments (25–60 minutes)

Focus: CFA Development

As a team, decide what types of CFAs will best measure the learning targets (e.g., quizzes, performance tasks, short written responses, 3-2-1 Reflections, or other CFA ideas).

- Split into smaller groups or pairs to begin designing these assessments (based on learning targets).

- Once drafts are ready, regroup to review, give feedback, revise, and finalize each CFA together.

Step 5: Calendar/Plan Dates for Implementation and Analysis (5–10 minutes)

Focus: Alignment of Learning Targets, CFAs, and Analysis

As a team, coordinate the calendar to ensure all teachers are addressing the same learning targets during the same weeks. This allows for meaningful and aligned data analysis across classrooms.

- Agree upon CFA implementation dates and schedule data analysis sessions to occur shortly after CFAs are given, ideally within 48 hours of implementation.

Step 6: Start the Intervention Document (25–60 minutes)

Focus: Intervention Plans

Have a MTSS (Multi-Tiered System of Supports) Framework document. Here are some resources for MTSS development. If you do not have a MTSS document, we start the process by ensuring that all students receive content equitably (Tier 1). Students are sorted into three categories for learning target mastery: “Struggling,” “Getting it,” or “Got it.” All students are provided with an intervention or extension activity the class period following student work analysis. (Teacher Tip: I use AI to create three different activities with different levels of scaffolding and modify as needed). These activities should be short-and-sweet, and a review of the CFA should occur immediately before the intervention activities. My “Got it” students are provided with an extension activity and work in a group with limited help. My “Getting it” and “Struggling” students (Tier 2) are in different groups, but in close proximately so that I can work with both groups while they complete the interventions. Students who are still struggling after the intervention will need further intervention (Tier 3), usually not a content-related intervention. This is why MTSS is a useful intervention framework, it allows teachers to address students on multiple levels and target the issues related to “still struggling” students. I use a Student Learning Reflection and Support Contract which allows students to self-reflect and set goals, allows me to clarify expectations, speak to the student one-on-one, and address belonging, safety and wellbeing needs.

- Create intervention strategies that are realistic, manageable, and directly informed by your anticipated CFA data and unit structure.

Step 7: Implement, Collect Student Examples, Analyze Data

Focus: Teaching and Student Learning Analysis

Step seven is the traditional work of a teacher, except for collaboratively analyzing student work.

- Begin teaching the content according to your pacing plan.

- Administer the agreed-upon CFA to students.

- After administering the assessment, reconvene with your team to analyze the student data collectively, looking for trends, gaps, and successes.

Our department analyzes student work in a variety of ways. Some of us use digital CFAs and these automatically analyze student results in graphs or tables. I use a student work analysis protocol which requires good-old-fashioned paper (some of you may remember using this yourselves). After categorizing my student work into the three categories mentioned above (struggling, getting it, and got it), our team reviews each other’s student examples, we discuss our ideas/opinions on student work, and calibrate our expectations for categorization. We also discuss our observations for gaps in learning and exceptional work. This helps us to see what is working in our classes and often leads to best-practice conversations. There are many examples for conducting student work analysis but here is the protocol we started to use and it has led to some great conversations and modifications in practice. Here are some other options for student work analysis from ASCD.org.

Step 8: Plan Interventions (25–30 minutes)

Focus: Finalize Interventions

Using the CFA data, design or finalize short, focused interventions that are directly aligned to student needs. I prefer to implement these immediately after reviewing the CFA with students and explaining the categories and the interventions needed for each group to better understand or extend knowledge beyond the content. I would like to mention that categorizing students can be tricky. Some students see it as a “dumb” and a “smart” grouping system, So, I am very clear in my description of “on this assessment” and “maybe you were distracted” or “next time I want to see you in the “got it” group”, commentary. CFAs should be ungraded and an assessment of learning. We are shifting from “getting a good grade” on an assessment to “learning and showing learning” on an assessment. Interventions are an opportunity to learn something that was missed. This needs to be communicated in the classroom and students will eventually understand that the process is to learn, not to score well.

- Ensure that interventions include appropriate scaffolding based on the level of student understanding.

- Consult your MTSS framework to identify any students who may need additional support beyond academics, such as social-emotional or behavioral interventions.

Step 9: Implement Interventions

Focus: Ensuring Learning

- Implement the interventions within 48 hours of administering the CFA, if possible.

- Track and document students who did not demonstrate mastery. Continue to apply MTSS strategies for students whose struggles may be unrelated to content comprehension. Provide Tier 2 or Tier 3 interventions when necessary.

- After interventions, return to Step 7 to begin a new cycle of teaching, CFA implementation, data analysis, intervention, and instructional improvement as needed.

Step 10: Summative Assessment

Focus: Final Assessment of Learning

Administer a summative assessment that covers all collaboratively determined learning targets, along with any other goals the team agreed to assess. Analyze and decide on interventions for students who fail in mastering the learning targets.

Conclusion

This protocol helps our team to dive into the real work of a PLC. It is by no means the only thing you will need. As mentioned previously, we have attended many training courses, read books and articles, attended conferences, and have spent years working out the kinks in our PLC. Our leadership team is supportive and participatory and we all work to put student learning first. That is what makes us a professional learning community. We are continuing our learning as professionals while we are ensuring that students are learning using this model. It has worked for us, and we hope that it will help you get started on your collaborative journey in this often-isolated educational environment.

Gina Arias, Ed.D., is a teacher and resource teacher for educator effectiveness at San Ysidro High School in the Sweetwater Union High School District. She has more than 20 years of teaching experience, including serving as a curriculum coordinator, professional development coordinator, peer coach and department chair.

References

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting Professional Learning Communities at Work: New Insights for Improving Schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Jacobson, D. (2010). Coherent Instructional Improvement and PLC’s: Is it Possible to do Both? Kappan, 91(6), 38-45.

Hudson, Christopher. (2024). A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Effective Professional Learning Community (PLC) Operation in Schools. Journal of Education, 204(3), 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574231197364

Muhammad, A., & Eaker, R. (2024). The way forward: Plc at work and the Bright Future of Education. Solution Tree Press.

Yusra Jadallah Abed Khasawneh, Raghad Alsarayreh, Adnan Ahmad Al Ajlouni, Haitham

Mustafa Eyadat, Mohammad Nayef Ayasrah, & Mohamad Ahmad Saleem Khasawneh. (2023). An Examination of Teacher Collaboration in Professional Learning Communities and Collaborative Teaching Practices. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 10(3), 446–452.