Clinical support can be critical to healing trauma in children who attend our schools, but educators actually have an equally significant role to play in the healing process.

By Wanda S. Perez

As an adult survivor of childhood trauma, my role as an educator is forever intertwined with my interest in overcoming the impact of trauma. I know from personal experience that trauma can be transformed into healing and critical hope (Solomon and Siegel, 2003).

I am not alone as a survivor and educator who seeks to be an agent of healing in the lives of students. The impact of trauma or traumatic experiences can either be invisible or on full display in our schools, and is often compounded by other unmet physical and mental needs.

The truth is that trauma does not discriminate. Current studies show that one in four children experiences trauma (Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, Koss, Marks, 1998). With CT3, I work with schools across the country. Trauma is often used to explain classroom-level issues like poor student behavior and low achievement.

The question for most educators, especially teachers and school leaders, is, “What do we do?” And this is where we must begin…

“What do we do?”

Asking the question is a powerful first step. Studies show that many educators do not see themselves as agents of healing for children who have or are experiencing trauma (Anderson, Blitz, Saastamoinen, 2015). As a result, many of the educators I work with often think that trauma is something for professional counselors and psychologists to handle, or something they cannot impact in a real way. It is true that clinical support can be critical to the healing process and educators cannot provide the same type of therapeutic intervention as counselors. However, we, as educators, actually have an equally significant role to play in the healing process.

I realized in my first year as a teacher that my students would spend up to three times as much time with me as they would with their own parents. Of course, I could not replace the role of parent, but it became clear to me that I had a significant role in every child’s life. Every teacher has the ability to “do something” that can help a vulnerable child.

The question then becomes, “What can we really do in the face of situations that seem impossibly complex in the lives of children?” I faced that question every day as a principal, and now that I am a trainer of school leaders, instructional coaches and teachers, I answer that question every single day. The first part of the answer is to accept that our actions as educators already currently impact the process of healing. Our actions are never neutral; they either contribute to healing or take away from it.

Do my actions heal or harm?

Relationships are the key lever in healing and hope because they also have the capacity to harm and intensify trauma. Every teacher must determine how the relationship they build with each student has the potential to heal or harm.

For children who have or are experiencing trauma, there is no middle ground. The progression of their experience will continue toward healing or deepen the trauma. It is through this lens that teachers must consider their actions carefully.

A paradigm for healing relationships

The trauma-informed student-teacher relationship is one where safety, trust, choice, collaboration and empowerment are established and nurtured intentionally (Fallot and Harris, 2009). The most effective educators begin with actions that naturally build trust. For educators who need support in learning how to build trust that leads to choice, collaboration and empowerment, the No-Nonsense Nurturer® model offers a process for building relationships of high care and high expectations. The process must begin with honest reflection.

Teachers need to ask: How do I usually approach the relationship with my students? Do I enable because I know that my students have experienced trauma? Do I try to control my students because I am afraid of how experiencing trauma will cause them to react? Both the tendencies of enabling and controlling are pathways toward relationships that harm, not heal.

After reflection, teachers must plan carefully and follow through on sharing their own authentic selves from day one, and consistently and continuously throughout the year. As in all relationships, students will trust what they see, and that trust will deepen as they learn about you over time. Teachers who share the failures, hopes, challenges and joy of learning not only engender trust but model behavior that may be completely unfamiliar. Sharing your authentic self in a way that is appropriate for the age of the child is as instructive as any math or reading lesson.

Implementing high care

As a teacher and school leader, it was easy to care about my students. I didn’t always realize, however, what “high care” looked and sounded like, or how powerful it could be. As a teacher, I had to learn to articulate my emotions and I often failed to make my heart known to my students.

Showing students how much I cared was a learning process for me.

High care starts by showing genuine interest in the lives of students. This sounds simple, but as I partner with schools, I’ve noticed that this is the most overlooked aspect of the student-teacher relationship. The lack of time, or perceived lack of time, is often to blame and can be overcome with intentionality and the implementation of culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995).

Showing interest is different than having fun. Fun and joy in the classroom is important, but interest in students’ lives is deeper and transformational. The action of showing interest is carried out through careful, active listening that does not project or enmesh the teacher’s trauma, identity or values on the experiences and feelings of the students.

Listening demonstrates high care to students. By listening and opening the space for student voice, teachers also offer validation that healing is a dynamic, imperfect process to not define the child but is simply part of their story. In no way is it the end of their story.

Teachers who can see through the trauma and beyond it, radiate acceptance of the productive struggle and character of the child. These actions provide children with the opposite of trauma; they provide empowering care that contributes to hope and healing.

Implementing high expectations

With high care, the door opens for high expectations. It is important to note that one without the other can cause harm. When coaching teachers to implement the No-Nonsense Nurturer model, or working with principals on their schoolwide culture, I often hear the question, “How can this child learn with all that has happened to them?” It is an understandable question when our adult brains process our own potentially unresolved trauma or learned helplessness, or if we experience our students’ trauma by proxy.

My own personal experience informs my answer. During my childhood years, I would have only been harmed further if I had attended a school that expected less of me. Not only would I have had to heal emotionally, but academically I would have lost access to my future and to a living wage.

Lowering academic expectations would not have helped me heal. This applies to behavioral expectations as well. While children will need understanding and systems of behavior interventions, the solution cannot be to condone disengaged or off-task behaviors that hinder learning.

Lowering expectations amounts to malpractice on the part of the teacher and school. When a teacher determines that a child is incapable of mastering the content needed to achieve academic success, he or she will only compound the effects of trauma (Bloom, 1995).

We can build relevance in our academic experiences by using trauma-informed literature, celebrating student voice and expression, and bringing the real lives of students authentically into the classroom as part of the curriculum. Research shows that literature selection combined with discussion groups benefits every student in the classroom. The universality of the approach and the themes in a student discussion group yielded lowers anxiety symptoms in students who had experienced trauma, but also provided non-traumatized students with unique insights into character motivation and other literary nuances (Rowley, 2016).

This is how we combine high care and high expectations.

Language and identity: Two keys to high care and high expectations

Two additional but major keys to showing high care and high expectations that heal include the use of intentional language and an understanding of identity formation.

To access hope and form healthy coping skills that generate resilience, children must also build a strong, healthy perception of self. It is well understood that children gain self-esteem from their experiences within families and other critical relationships, including those at school.

Even in less traumatic settings, positive identity formation can be challenging. For children who have experienced trauma, self-blame, self-harm and isolation, this negatively impacts their identity and sense of hope (Cammarota, 2011). To promote healing and learning, teachers must support positive self-perceptions and model an overall attitude of hope through specific language and cultural competence (Berger, Gelkopf, Heineberg and Zimbardo, 2016).

The most impactful use of language is praise and attention, but good intentions can unintentionally trigger trauma. Children who have experienced trauma sometimes perceive empty praise as manipulation, which destroys trust. While encouragement and attention are important, overdoing it does not necessarily accelerate healing.

Too much attention can trigger a flight-or-fight reaction. This also serves to empower, not create a learned helplessness (Fecser, 2015). Frequent, short positive interactions during classroom time are often best.

In the No-Nonsense Nurturer model, providing precise directions and positive narration, along with transparent and consistent consequences and incentives, ensures that the language a teacher uses builds trust, safety and does not trigger a flight-or-fight reaction from students.

It is critical to note that even the best words will fail without a sense of hope, joy, emotional consistency and authenticity. Children feel words and they are amazing “lie detectors.” Teachers must back up the specificity of language and contributions to identity formation with high care and high expectations. All aspects of the relationship work in concert.

Another opportunity to build positive self-identity and hope in students is to build knowledge and understanding of the cultural context that makes up part of a child’s identity. This connects to the formation of an effective relationship, which communicates trust and acceptance of the child. Children need to witness a level of understanding and acceptance of their culture in their classrooms in order to feel secure. It is impossible to build a relationship of trust without making intentional attempts to understand the cultural norms of a child.

When teachers have an implicit bias against a culture, whether or not they realize it, this often transfers to the relationship with the child. This can also trigger a child and further deepen the effects of trauma. If a teacher shares cultural activities and norms, and acknowledges positive aspects of a child’s cultural context, it serves to rebuild aspects of identity that have been torn down by trauma, especially self-worth (Macy, et al. 2003).

Many teachers struggle to put into action cultural competence because they feel that they don’t have enough time or lack understanding of how to build culturally relevant pedagogy. The key actions already outlined can begin to change these familiar obstacles. Remember: high care and high expectations. Be a student of your students by showing genuine interest in their lives. Pull the lever of literature as a transformative medium for relevance and rigor.

Moving toward actions that heal

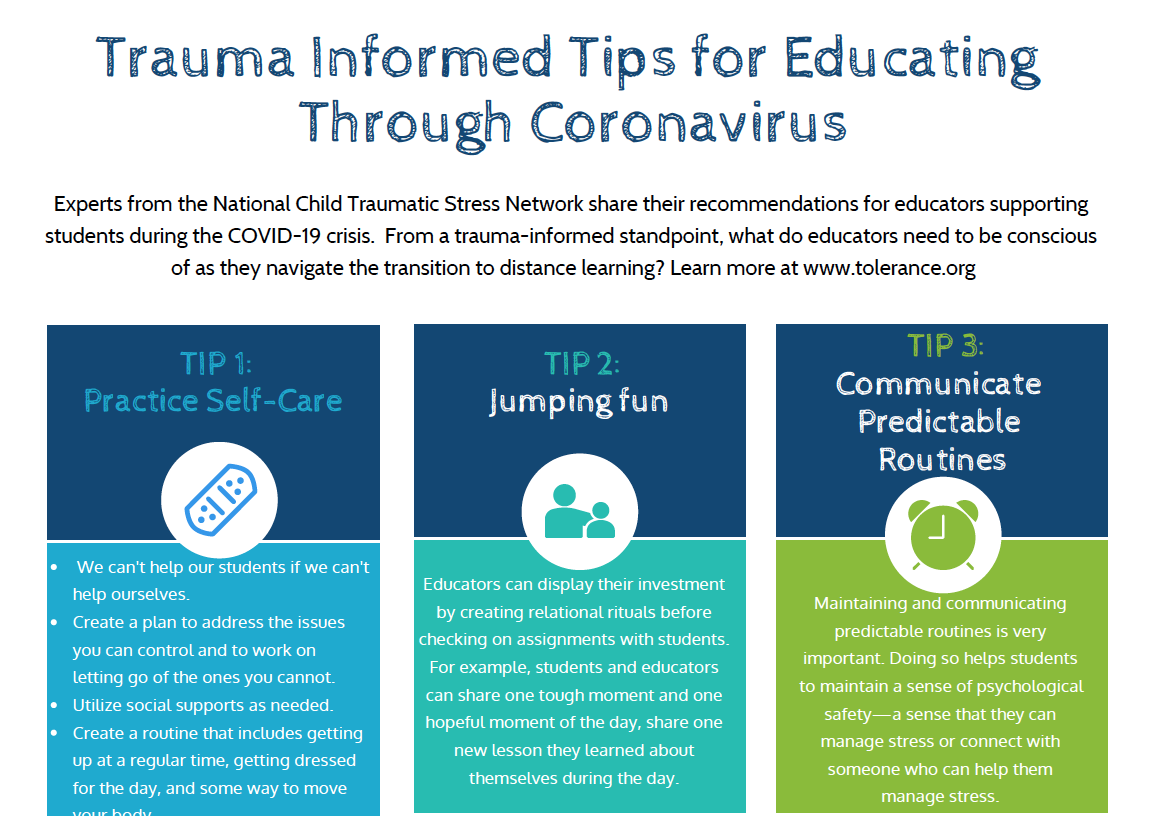

Beyond the lack of tools, knowledge and support, the reality for teachers is that trauma can be traumatizing. I do not say this sarcastically or to minimize the fear and effort of engaging in this work. As a community of educators, we must accept the challenge and seek out self-care in order to inspire healing and hope in our students.

Therefore, I offer a final charge. Talk to one colleague about the role that trauma has played or plays in your life as an educator and person. Ask the critical questions, start the reflection and commit to moving toward action. Join me in the journey. Perhaps one day, every educator given the tools, knowledge and support will evoke actions that promote healing in their classroom.

Resources

Anderson, E.M., Blitz, L.V. and Saastamoinen, M. (2015). “Exploring a school-university model for professional development with classroom staff: Teaching trauma-informed approaches.” School Community Journal, 25(2), 113-134.

Berger, R., Gelkopf, M., Heineberg, Y. and Zimbardo, P. (2016). “A school-based intervention for reducing posttraumatic symptomatology and intolerance during political violence.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 761-771. doi:10.1037/edu0000066.

Bloom, S.L. (1995). “Creating sanctuary in the school.” Journal for a Just and Caring Education, 1(4), 403.

Cammarota, J. (2011). “From hopelessness to hope: Social justice pedagogy in urban education and youth development.” Urban Education, 46(4), 828-844. doi:10.1177/0042085911399931.

Crosby, S.D. (2015). “An ecological perspective on emerging trauma-informed teaching practices.” Children & Schools, 37(4), 223-230. doi:10.1093/cs/cdv027.

Fallot, R.D. and Harris, M. (2009). “Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care (CCTIC): A self-assessment and planning protocol.” Washington, DC: Community Connections. Retrieved from http://www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/icmh/documents/CCTICSelf-AssessmentandPlanningProtocol0709.pdf.

Fecser, M.E. (2015). “Classroom strategies for traumatized, oppositional students.” Reclaiming Children & Youth, 24(1), 20-24.

Felitti, V.J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D.F., Spitz, A.M., Edwards, V., Koss, M.P. and Marks, J.S. (1998). “Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). “Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy.” American educational research journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Lelli, C. (2014). “10 strategies to help the traumatized child in school.” Kappa Delta Pi Record, 50(3), 114-118. doi:10.1080/00228958.2014.931145.

Macy, R.D., Mary, D.J., Gross, S.I. and Brighton, P. (2003). “Healing in familiar settings: Support for children and youth in the classroom and community.” New Directions for Youth Development, 2003(98), 51-79.

Rowley, K. (2016). “Coming of age in the united states: A case for differentiating curriculum as a response to trauma.” California English, 22(1), 10-11.

Solomon, M.F. and Siegel, D.J. (2003). “Healing trauma: attachment, mind, body, and brain.” New York: W.W. Norton.

Solar, E. (2011). Prove them wrong. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(1), 40-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005991104400105

Statman-Weil, K. (2015). “Creating trauma-sensitive classrooms.” YC: Young Children, 70(2), 72-79.

Wanda S. Perez, M.Ed. has served as a teacher, administrator and school board member. As a principal in Washington, D.C., Perez led change in curriculum, talent management, bilingual program design and school culture; resulting in a 55-point gain in math and a 32-point gain in reading from 2007 to 2013. Perez holds a post-graduate certificate in supervision and administration from Johns Hopkins University and a master’s in elementary education from Towson University. She is currently pursuing an Ed.D at Northeastern University and is a lead associate at San Francisco-based CT3.